How to Choose Outcomes for an Evidence Table: Quantitative vs Qualitative Reviews

TL;DR

Most evidence tables fail before extraction even begins — because outcomes are chosen without thinking about how the data will be analysed.

When selecting outcomes, start with the decision your review needs to support, then design outcomes around the planned synthesis.

- For quantitative reviews, choose outcomes that are comparable, measurable, and analysable across studies.

- For qualitative reviews, define a small set of decision-relevant phenomena that capture experiences, acceptability, and implementation context.

Extracting more data is rarely the problem.

Extracting outcomes that cannot support analysis is.

When teams in HTA, pharma, or HEOR struggle with evidence tables, the problem rarely starts at extraction.

It starts earlier.

Most evidence tables fail before extraction even begins because outcome selection is done without thinking about how the data will actually be analysed, compared, or used to support a decision.

This article explains how to choose outcomes deliberately, depending on whether your review will use a quantitative or qualitative approach, and why outcome selection is one of the highest-leverage decisions you make when building an extraction form.

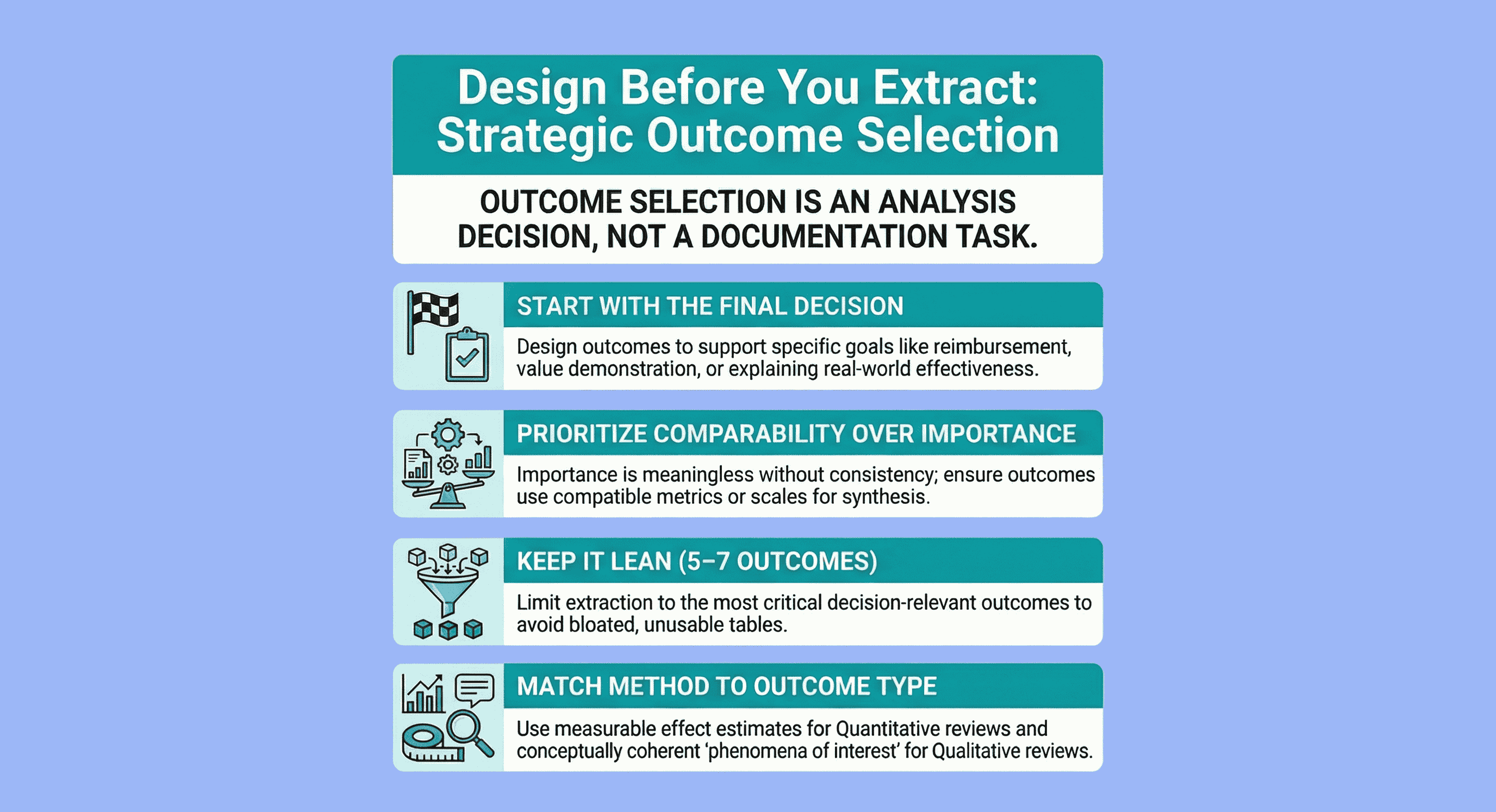

Outcome selection starts with the decision the review must support

Before thinking about rows, columns, or extraction templates, ask one question:

What decision must this evidence table ultimately support?

For HTA and HEOR teams, that decision is usually one of the following:

- Comparative effectiveness for reimbursement or access decisions

- Value demonstration versus standard of care

- Understanding uncertainty, heterogeneity, or evidence gaps

- Explaining why an intervention works (or fails) in real-world settings

If outcomes are selected without a clear decision context, the result is predictable:

- Bloated extraction forms

- Inconsistent reporting across studies

- Tables that look complete but are analytically unusable

Outcome selection is not a documentation task.

It is a design decision. (see Getting Started with Evidence Tables.

A core principle: think about analysis before extraction

The most common mistake I see in HTA and pharma projects is simple:

Outcomes are chosen based on what studies report, not on what can be analysed.

Extraction forms are often built by scanning a handful of papers and adding every outcome that appears “important”.

The problem is that importance is meaningless without comparability.

Before finalising outcomes, you should already be able to answer:

- Will this outcome be synthesised quantitatively, narratively, or not at all?

- Will results be pooled, compared across subgroups, or only described?

- Will different instruments, definitions, or time points break comparability?

If those questions feel premature, that’s the warning sign. (see Best Practices for Data Extraction in Systematic Reviews)

General principles for choosing outcomes (regardless of approach)

Some rules apply to all evidence tables, whether quantitative or qualitative:

- Outcomes must be derived from the review question and decision context, not from convenience

- Prioritise outcomes that are decision-relevant for payers, HTA bodies, clinicians, or patients

- Limit the number of critical outcomes (typically 5–7 per comparison)

- Explicitly plan for benefits and harms, even if data are expected to be sparse

One important clarification for HTA teams:

It is usually better to extract more data than less,

as long as outcomes are structured and analysable.

The mistake is not extracting “too much”.

The mistake is extracting without structure or intent.

Choosing outcomes for a quantitative approach

If your review will involve a meta-analysis or other quantitative synthesis, outcomes must meet one non-negotiable requirement:

They must be comparable across studies.

What this means in practice

When selecting outcomes for quantitative extraction, favour outcomes that:

- Are reported using compatible metrics or scales

- Can be transformed into effect estimates (RR, OR, HR, MD, SMD)

- Have clearly defined time points

- Are reported consistently enough to allow pooling or structured comparison

If multiple instruments exist for the same construct (e.g. symptom severity, quality of life), you must decide in advance:

- Which instruments will be prioritised

- Whether standardisation (e.g. SMD) will be used

- How responder definitions will be handled

Failing to pre-decide this is one of the main reasons meta-analyses collapse late in the process.

Typical quantitative outcome domains

For HTA and HEOR-focused reviews, quantitative evidence tables commonly include:

- Primary clinical outcomes (e.g. mortality, progression, response rates)

- Patient-reported outcomes and quality of life

- Safety and tolerability (adverse events, discontinuation)

- Resource use or cost-related outcomes, where relevant

Each outcome should map cleanly to:

- Effect estimates

- Number of studies and participants

- Risk-of-bias or certainty assessments

If an outcome cannot reasonably support these columns, it probably does not belong in a quantitative table.

Choosing outcomes for a qualitative approach

For qualitative evidence synthesis, the word “outcome” can be misleading.

Here, outcomes are better understood as phenomena of interest.

How qualitative outcome selection differs

In qualitative reviews, you are not extracting numbers.

You are extracting meaning, experience, and context.

Outcomes should reflect:

- Lived experience of interventions or services

- Acceptability, feasibility, and implementation barriers

- Perceived benefits and harms from the participant perspective

- Organisational or system-level influences on effectiveness

The key difference is that:

- Quantitative outcomes must be comparable

- Qualitative outcomes must be conceptually coherent

You should still define a small number of core phenomena in advance, even though themes may evolve during synthesis.

Planning for certainty in qualitative evidence

HTA-relevant qualitative tables should also plan for:

- Contribution of individual studies

- Coherence of findings

- Adequacy and richness of data

- Relevance to the decision context

Without this structure, qualitative findings risk being dismissed as “interesting but inconclusive”.

Matching the evidence table structure to the synthesis approach

Outcome selection and table structure are inseparable.

- Quantitative tables prioritise effect sizes, comparators, sample sizes, and certainty by outcome

- Qualitative tables prioritise themes, contributing studies, illustrative data, and confidence in findings

- Mixed-methods reviews often require two linked tables aligned to the same high-level outcome domains

When tables are aligned to analysis from the outset, synthesis becomes faster, clearer, and defensible.

Why this matters for HTA and HEOR teams

In HTA, evidence tables are not academic artefacts.

They are decision infrastructure.

Poor outcome selection leads to:

- Fragile meta-analyses

- Narrative syntheses that lack credibility

- Extra rounds of clarification with reviewers or payers

- Missed opportunities to demonstrate value

Strong outcome selection does the opposite:

- It reduces downstream rework

- Improves confidence in conclusions

- Makes uncertainty explicit rather than accidental

Final thought

If there is one idea to take away, it is this:

Outcome selection is an analysis decision, not an extraction decision.

When outcomes are chosen with synthesis in mind, evidence tables stop being static spreadsheets and start functioning as what HTA and HEOR teams actually need:

Tools for making defensible, high-stakes decisions.

Tags:

About the Author

Connect on LinkedInGeorge Burchell

George Burchell is a specialist in systematic literature reviews and scientific evidence synthesis with significant expertise in integrating advanced AI technologies and automation tools into the research process. With over four years of consulting and practical experience, he has developed and led multiple projects focused on accelerating and refining the workflow for systematic reviews within medical and scientific research.